While some home invaders are unwelcomed guests, the annual visit by field crickets always provides a bit of alright for me.

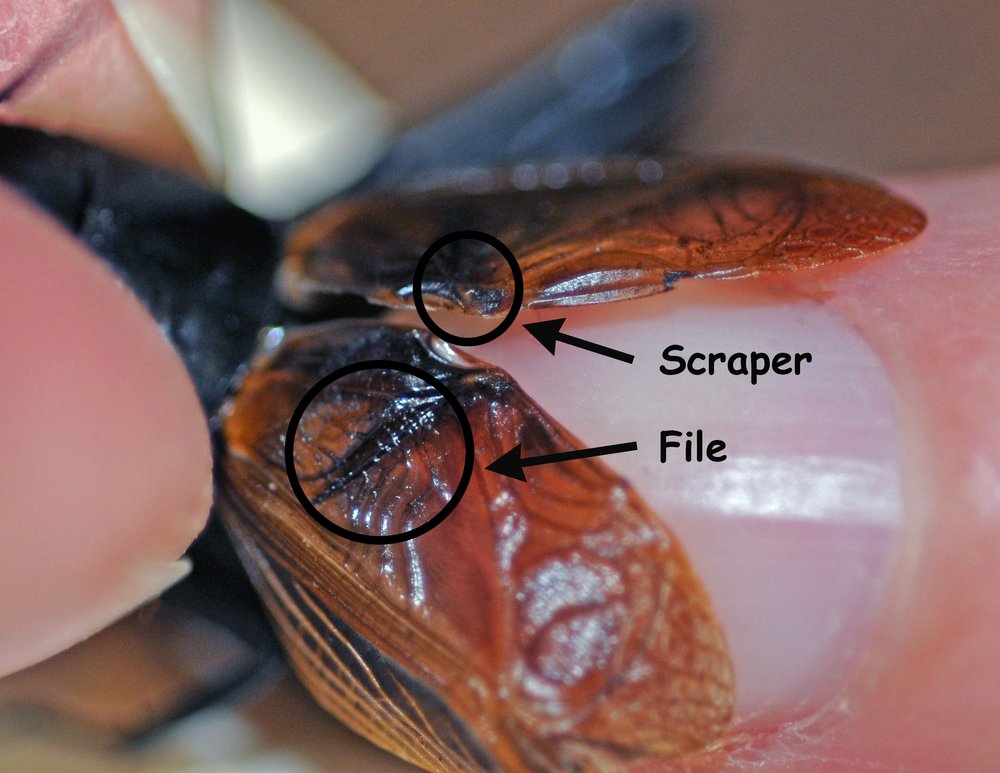

Melodious male crickets bear a multi-ridged structure called the file on one forewing. The opposite forewing bears a hardened structure called the scraper. As wings open and close, the file moves across the scraper creating vibrations, or chirps, that resonate from the cricket’s wings.

Despite my profound fondness for almost all things six-legged, a 4:30 am wake-up call courtesy of a field cricket in the bathroom did make me a bit peevish. It also heralded the vanguard of the usual annual invasion of arthropods that assault my home each autumn. With sleep seriously disturbed, I seized the opportunity to see how well chirps of this diminutive troubadour tracked ambient temperature. Here’s the backstory of how it works. As you know, insects are cold blooded. Their body temperature is more or less the same as the environment that surrounds them unless the insect is basking in the sun or using muscles to elevate its temperature like the dobsonfly we met in a previous episode. Many years ago, a noted entomologist, Richard Alexander, demonstrated a simple relationship between ambient temperature and the how often a field cricket chirped. Simply count the number of chirps in 15 seconds, add 37, and you will approximate the ambient temperature in degrees Fahrenheit. Although I tracked down the diminutive troubadour behind the toilet, he developed a severe case of stage-fright when he saw the camera and refused to perform. Undeterred from my quest, I slipped on a pair of crocs and went outside where a complete ensemble of field crickets chirped away in the flower bed. Darkness prevented visual contact with the crickets but their songs were loud and easily recorded. I selected two singers and recorded each 20 times at intervals of 15 seconds. A rather warm-blooded cricket averaged 34 chirps per 15 seconds which estimated the temperature to be 71 degrees (34 + 37 = 71). Nearby a cooler cat reported in with 28 chirps per 15 seconds, estimating the temperature to be 65 (28 + 37 = 65). A digital thermometer placed on the ground in the flower bed showed an ambient temperature of 69 degrees. One cricket too warm, one cricket too cool, but when you take the average, just as like in Goldilocks and the three bears, the average cricket estimate of 68 was just about right.

While my sleep-interrupted cricket failed to perform, on another occasion a less shy field cricket was happy to tell me the temperature inside my home. Watch the accompanying video to see how well he estimated the temperature on my kitchen counter.

This little field cricket demonstrates his skill at helping humans estimate ambient temperatures. Counting the number of chirps in 15 seconds and adding 37 provides an estimate of ambient temperature. Let’s see how well this works: 32 chirps plus 37 equals 69 degrees Fahrenheit. My digital thermometer read 73 degrees above the kitchen counter. Maybe this little guy was just a cool customer.

Although some might think so, helping humans figure out ambient temperature is unlikely the reason why crickets chirp. A few years ago, I tracked two male crickets, one of which was missing a hind leg, and a nearby female cricket. Never one to stand in the way of romance, I captured the trio and placed them in a small terrarium. Within moments the smaller male, the five-legged fellow named Pete, challenged his cohabitant, Bud, to a duel that resulted in boisterous chirping, snapping of jaws, and grappling with forelegs. The more aggressive Bud soon vanquished his challenger and Pete retreated to a quiet corner of the terrarium. Crickets battle for food and mates and chirping is a part of this. For centuries Chinese gamblers have wagered high stakes on the outcome of cricket fights. An interesting trick used by the cricket handlers to resuscitate losers of bouts is to shake the defeated warriors and toss them in the air several times. This dramatically reduces the recovery time and allows the small combatants to return to the arena in minutes rather than the regular convalescent period of hours or days. A study published in Nature confirmed the success of this therapy in helping defeated crickets regain their fighting spirit.

In addition to wooing mates, some cricket chirps warn interlopers to get lost!

Rather than interrupt Nature’s course, I allowed Pete to sulk in the corner. Shortly after his victory, Bud initiated a series of soft chirps and his efforts were soon rewarded by a visit from Wendy, the demure female cricket. What useful information is carried in the male cricket’s song other than the typical male plea for female attention? A fascinating study by two Finnish scientists of the Mediterranean field cricket, Gryllus bimaculatus, found a link between the male cricket’s song and his immune response. Troubadours with a highly attractive song also had superior immune systems. If the ability to ward off diseases due to superior immune function is passed along to progeny, then females that choose a mate with an enhanced immune system may ensure better survival of their offspring. By demonstrating his superior immune system with a song, the male cricket may win the lady.

One last thought about the cricket and his song relates to Old Man Winter, whose return brings much insect activity to a grinding halt. Once winter’s chill arrives and temperatures plummet, crickets will not be chirping at all. So, now is a great time to enjoy songs of crickets, day and night, maybe even those reverberating from troubadours in the bathroom.

Acknowledgements

The following articles were used in preparation for this Bug of the Week: “Courtship song and immune function in the field cricket Gryllus bimaculatus” by Markus Rantala and Raine Kortet, “Aggressiveness recovers much faster in male crickets forced to fly after a defeat” by Hans A. Hofmann and Paul A. Stevenson, and “Seasonal and daily chirping cycles in the northern spring and fall field crickets Gryllus veletis and Gryllus pennsylvanicus” by Richard Alexander and Gerald Meral.

No comments:

Post a Comment