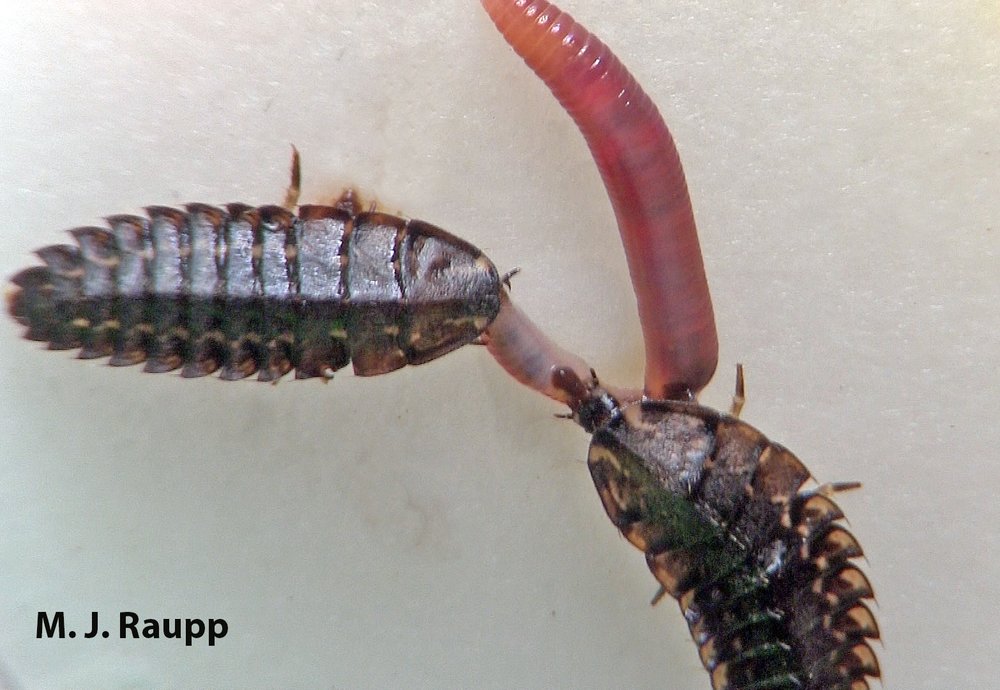

A pair of glow-worms team up to enjoy a tasty earthworm meal.

Earlier this year we met fantastic fireflies. They appeared to enjoy a very good year in many parts of the DMV, including my yard in Columbia, MD. In addition to serving as a way to find a mate, the bioluminescence of fireflies also serves as a warning signal to predators. Attacking this tempting, flashy meal could turn out to be a nasty surprise. You see, many species of fireflies are chemically protected and rendered unpalatable by noxious chemicals known as lucibufagins. Last week while enjoying a moonlit stroll along the towpath of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal which boarders the mighty Potomac River, eerie green lights winked on and off amongst the vegetation. Upon closer inspection, the source of this spectral display turned out to be generated by the immature stages of fireflies, larvae called glow-worms. Unlike the vivid light produced by adult fireflies, the C&O glow-worms produced an intermittent spark of soft, greenish light. Judging by their size, these largish larvae were likely the offspring of fireflies that deposited eggs in the soil during the summer of 2023. Many glow-worms in our region require two summers to develop.

Along a towpath bordering the banks of the mighty Potomac River, eerie green lights on the ground mark the location of glow-worms. The red dot is produced by the video camera. Light is produced by white luminescent organs beneath the abdomen of the larva. Daylight gives us a better look at the fast-moving glow-worm. Watch as a pair of glow-worms feast on an earthworm. Neurotoxins injected into the worm through sharp hollow jaws immobilize the prey. Digestive enzymes secreted by the larva liquify the worm’s tissues, and then the glow-worms slurp their liquid feast. Glow-worms help rid our gardens of pests like slugs, snails, and other soil-dwelling insect pests.

Glow-worms produce their eerie lights with paired luminescent organs on the underside of their abdomen.

We all have heard the tales of fireflies using distinct patterns and colors of luminescent flashes to recognize and find mates. But why would juvenile beetle larvae engage in flashy displays? These youngsters were obviously too young for the adult firefly mating game. Scientists discovered that immature stages of fireflies, glow-worms, like their adult counterparts, are also distasteful to many kinds of predators including ants, birds, rodents and amphibians. Their eerie flashing lights serve as a warning to hungry would-be predators not to attempt an attack unless they desire nasty tasting meal. Paired luminescent organs on the underside of the glow-worm’s abdomen produce the green light, which serves as a warning.

In addition to being a little creepy and pretty cool, glow-worms are highly beneficial in your garden and in crops where they eat many soft-bodied invertebrates including slugs, snails, and other soil-dwelling insect pests. I invited a pair of glow-worms into my home to spend a little time with me. Over the course of several days, they consumed many types of prey, including maggots and earthworms. Some of the earthworms were quite large and I wondered how they wrangled large prey. It turns out that glow-worms use sharp hollow jaws to inject prey with paralyzing neurotoxins. Once immobilized, digestive enzymes are secreted via their mouthparts into the victim to help liquify its body tissues. The resulting nutrient rich broth is then slurped up into the larva’s digestive tract. Yum!

If you enjoyed fireflies in your landscape this summer, consider taking a walk outdoors on a starlit night and maybe you will be treated to the ethereal light of the glow-worms in your lawn or flower bed.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Dr. Shrewsbury for providing text used in this episode and wrangling glow-worms featured herein. The fascinating writings “Bioluminescence in Firefly Larvae: A Test of the Aposematic Display Hypothesis (Coleoptera:Lampyridae)” by Todd J. Underwood, Douglas W. Tallamy, and John D. Pesek, and “ Glow-worm larvae bioluminescence (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) operates as an aposematic signal upon toads (Bufo bufo)” by Raphael De Cock and Erik Matthysen, “Flash Signal Evolution, Mate Choice, and Predation in Fireflies” by Sara M. Lewis and Christopher K. Cratsley, “How to Overcome a Snail? Identification of Putative Neurotoxins of Snail-Feeding Firefly Larvae (Coleoptera: Lampyridae, Lampyris noctiluca)” by Jonas Krämer, Patrick Hölker, and Reinhard Predel, and “For the love of insects” by Thomas Eisner served as resources for this Bug of the Week.