In regions infested with spotted lanternflies bright red nymphs (left) are molting into adults (right) ready for mischief.

Vegetation beneath trees infested by spotted lanternflies glisten with honeydew excreted by lanternflies as they suck sap from trees.

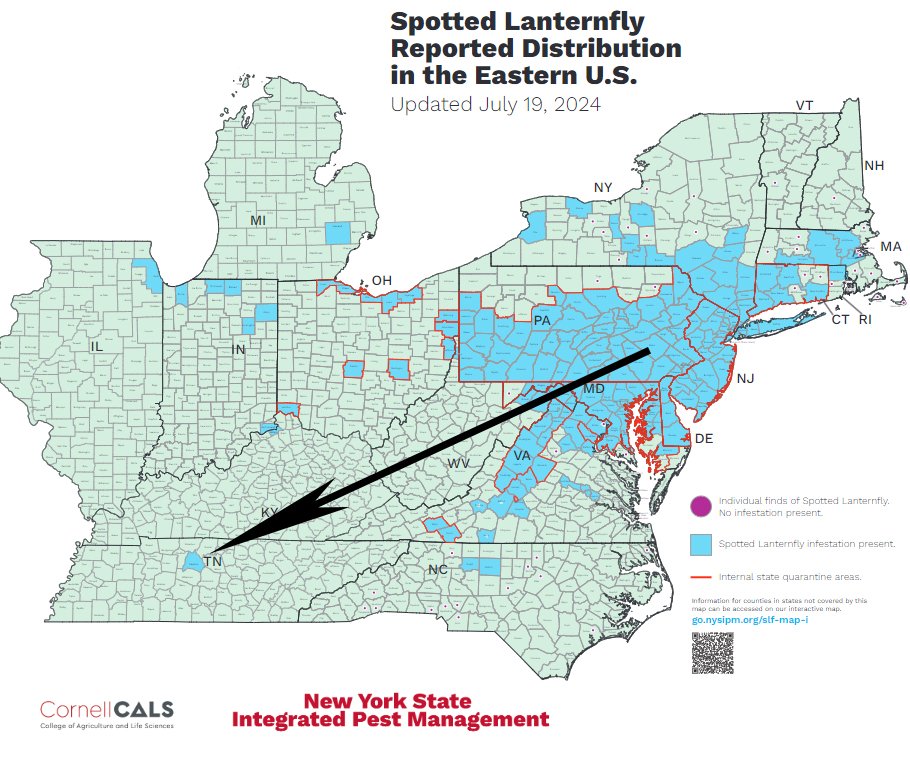

Last week inquiries poured in regarding hordes of brilliant red insects bespeckled with white spots and black patches aggregating on trees and dashing across lawn furniture and buildings. These are the fourth juvenile feeding stage, a.k.a. nymphal stage, of the despicable spotted lanternfly. In slightly cooler locations in Maryland like Hagerstown and Cumberland the majority of lanternflies were nymphs last week, but in warmer locations like Columbia and College Park youngsters has transitioned to sap-sucking adults. The deluge of honeydew excreted by lanternfly nymphs and adults as they feed has begun, fouling underlying vegetation and attracting stinging insects. The most frequently asked question over the past week or two has been, why are we seeing more lanternflies? At least three reasons help us understand. First, let’s go back a decade to spotted lanternflies’ original detection in Berks County, PA. In the intervening decade, spotted lanternfly has established and is reproducing in more than a dozen states with some infestations more than 600 miles distant from Berks County. More people are encountering lanternflies simply because they now occupy a much larger geographic area in the US.

In areas infested with spotted lanternflies, bright red nymphs are molting into adults. In Columbia, Maryland, the deluge of honeydew excreted by lanternflies has begun. Honeydew rains down from trees, forming pools and fouling objects below. Sugar-rich honeydew attracts many types of stinging insects including paper wasps, yellowjackets, European hornets, and honey bees. Get ready for lanternfly showers and be careful around stinging insects.

Second, as lanternflies spread either by natural means or potentially over hundreds of miles with human assistance, new colonies become established. New infestations might be founded by small numbers of undetected egg masses, each with 30 to 60 eggs, that hitched a ride on some lawn furniture or maybe a metal sculpture. For a number of years these few pioneers might be off the radar, undetected, as was the case with the initial introduction of spotted lanternflies in Pennsylvania. With abundant food sources like the invasive tree of heaven, numerous herbaceous and woody plants and low levels of predators, parasites, and pathogens tracking their burgeoning population, lanternfly populations can enjoy a period of exponential growth. As satellite colonies merge along the ever-expanding lanternfly front and as populations rise in the generally infested area, more people encounter spotted lanternflies.

Since its discovery in Berks County, PA a decade ago, with human assistance the spotted lanternfly has moved more than 600 miles to several states.

Third, bigger insects are more commonly noticed than smaller ones. Tiny lanternfly nymphs hatching from an egg are but a few millimeters long. They scuttle about vegetation on the forest floor and low-lying shrubs feeding on more than a 100 plant species. However, by July, brilliant red nymphs have molted into tawny coated adults an inch or more in length. Being more than 20 times larger than youngsters, they are more readily noticed as they cluster on the trunks of trees or take flight as they move about the landscape in search of food, mates, and places to deposit eggs. In reality, due to high juvenile mortality of nymphs, which is the hallmark of most insect species, there are actually far fewer lanternflies now than there were back in May when eggs first hatched. Readers will certainly find no solace in this.

Sugar-rich honeydew excreted by spotted lanternflies attracts yellow jackets and other stinging insects.

What’s next for spotted lanternfly here in the DMV and around the land? Hordes of adult lanternflies and their attendant deluge of honeydew abound in my neighborhood in Columbia, MD. Underlying vegetation is drenched by sweet sticky honeydew which provides a substrate for sooty mold to grow and soon turn leaves and stems black. The sugar junkies, wasps and bees, have arrived to enjoy the carbohydrate bounty.

Is there any good news here? As we learned last autumn, scientists at Penn State documented more than 1000 attacks by spiders, mantises, birds, and other predators of spotted lanternflies. Also getting in on the act are naturally occurring soil fungi that have caused at least one lanternfly population to collapse in Pennsylvania. Here’s hoping Mother Nature sends some of this help our way soon.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Lisa Robinson and Jennifer Franciotti for providing the inspiration for this episode. Thanks also to Brian Eshenaur and the entire team at the New York State Integrated Pest Management Program of Cornell University for providing the updated maps of spotted lanternfly in the US. The fascinating article “A pair of native fungal pathogens drives decline of a new invasive herbivore” by Eric H. Clifton, Louela A. Castrillo, Andrii Gryganskyi, and Ann E. Hajek was used as a reference for this episode.

No comments:

Post a Comment