Guess which one is a maniacal predator ravaging prey in the stygian world beneath the bark of fallen trees.

As we settle into the coldest weeks of the winter, the search for insects outdoors becomes a little trickier than in summertime. Many insects here in the DMV have migrated to warmer lands or hunkered down in hibernal refuges to survive winter’s chill. One reliable place to find fascinating insects any season of the year is beneath the bark of fallen trees. So, on a 24-degree morning last week I combed the banks of the Patuxent River in search of recently downed oak trees, those in an early stage of decomposition with bark still clinging to underlying wood. Beneath the bark, nutrient rich tissues are home to myriad wood decaying fungi and scores of insects that consume not only decomposing wood but luxuriant fungal hyphae and fruiting bodies. In this realm of decomposers, voracious predators prowl in search of the tender flesh of other insects.

A mating pair of eyed elaters greet a predator or camera with four spooky eyes.

The first two oaks I encountered yielded a few tiny fly larvae but nothing more. Under the bark of a third fallen oak, an almost fully-grown larva of the eyed elater rested in a state of winter torpor. These fierce predators hunt other insects such as the larvae of flies, caterpillars, and other beetles living in the dark voids beneath bark. Powerful jaws of the eyed elater larva capture and dismember prey. After consuming a full complement of victims and completing its juvenile development, the larva transforms into the magnificent eyed elater, also known as the eyed click beetle. One look at this big beauty (up to 1 ½ inches long) provides instant understanding of how “eyed” became part of its name. As you stare at the beetle, two large and impressive eyes stare back at you. But these are not true eyes. The real compound eyes are rather small and located on the head of the click beetle near the base of the antennae. The markings on the back of the beetle are false eyespots like those we have seen on other guests of Bug of the Week, like the Polyphemus moth, swallowtail butterfly larva, and owl butterfly. The beetle’s strange and ghostly eyespots are thought to startle or confuse predators such as birds or other reptiles that might want to make a meal of a large, tasty beetle.

Beneath the bark of recently fallen trees thrives a rich ecosystem of fungi, insects, and microbial decomposers of wood. Larvae of the eyed elater are ferocious invertebrate predators high in the food web of these hidden realms. Bringing a chilly eyed elater larva indoors for a brief warm-up allows one to see the powerful jaws of this awesome predator.

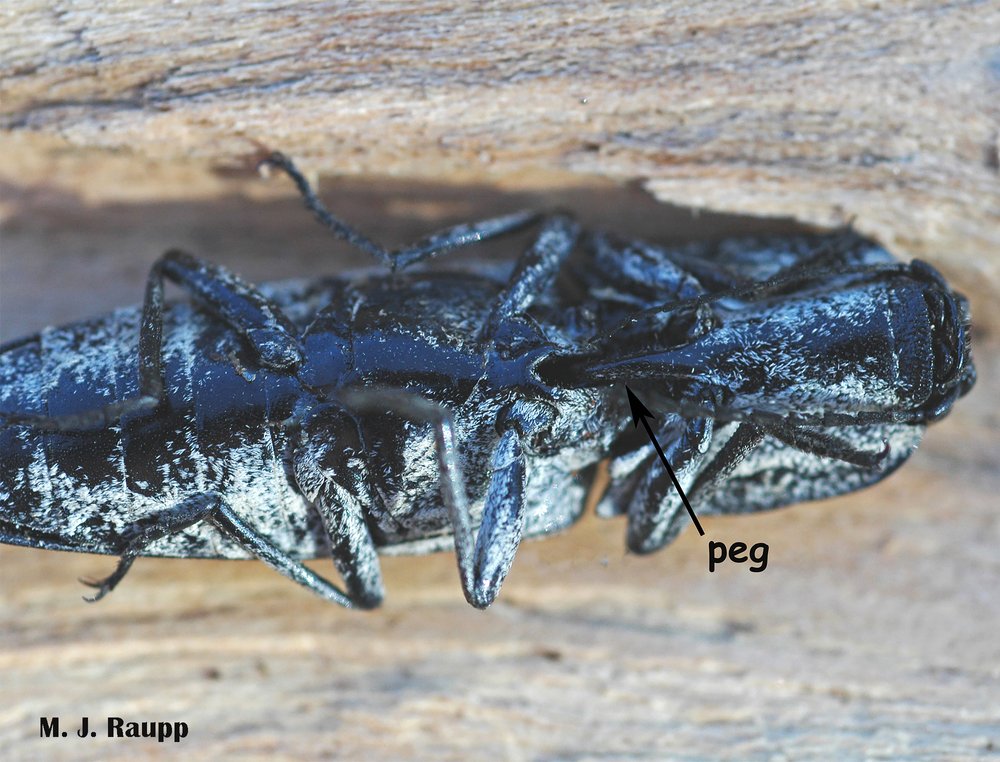

The peg on the underside of the click beetle is part of the remarkable system which propels the beetle into the air with an audible click.

That explains the business about the “eyed”, but what about the “click”? To understand the click, you must be lucky enough to find and capture a click beetle. When grasped by a geeky entomologist, the eyed click beetle produces an unnerving snap of its body. When placed on its back on the ground, this snap propels the beetle into the air. The acceleration of this flip can exceed 2,000 meters per second squared and shoot the beetle several inches into the air. How do they do this? Click beetles have a remarkable peg latch on the under-surface of their body between the front and middle legs. The beetle flexes its body creating tension that, when released, causes the front end of the beetle to snap backward, propelling the insect into the air with an audible click. The beetle often lands right side up, but if it doesn't, the click-and-flip process may be repeated until the beetle finally rights itself. Although the full reason for the beetle flipping-out is not fully known, we can speculate that this forceful snapping and flipping might help the beetle escape the grasp of a tormenting predator or nosy entomologist.

Listen for the audible ‘click’ as the eyed elater flexes up and down. With a powerful snap of its body, the eyed elater jumps several inches, often righting itself. An unsuspecting vertebrate predator or bug geek might have an unnerving surprise when encountering this lively insect.

One last etymological note regarding this interesting beetle has to do with the name “elater”, coined from the ancient Greek word for “that which drives away”, a fitting name for this clever beetle. Smaller, less dramatic click beetles are frequent visitors to our porch lamps in spring and summer. Click beetles are great fun to capture and most entertaining, but please put them back unharmed where you found them when you are done.

Acknowledgements

This remarkable video by Dr. Adrian Smith of the North Carolina State University provided great insight into the mechanics of propulsion used by click beetles. Watch his amazing video at this link: https://www.google.com/search?q=how+does+the+click+beetle+flip+up&oq=&aqs=chrome.2.69i59i450l8.697805522j0j15&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#kpvalbx=_HdLxYYrqCYCqptQP7OaeiAg15

The bible for identifying insect larvae and nymphs, “Immature Insects” by Frederick W. Stehr, was used to identify the larva of the eyed elater.

No comments:

Post a Comment