Cicadas insert soda-straw-like sucking mouthparts called a beak or proboscis into plant tissues to obtain nutrients for growth and development. Adult feeding results in minimal damage to plants compared to injury caused when female cicadas use their ovipositor to slit branches. Into these wounds eggs are deposited in egg-nests. Eggs develop during spring and summer. Cicada nymphs will hatch from these eggs, drop to the earth, and develop underground for the next seventeen years.

In recent episodes we learned where Brood XIV cicadas would and would not be seen this spring. We also discovered what signs to look for in your yard as a presage to their grand appearance. This week let’s tackle a few questions that popped up in a recent conversation with the Weather Channel. Two of the most frequently asked questions regarding cicadas is “do they bite and do they sting?” Well, through my six decades of watching, catching, studying, eating, and photographing cicadas, my answer has been no, don’t worry about being bitten or stung by cicadas. However, following two messages from folks who listened to a television interview this week, I am scratching my head just a little bit about what cicadas can and cannot do with regard to biting and stinging. One viewer recounted an episode almost two decades ago when a cicada landed on their shoulder and pierced the skin leaving behind a zig-zag shaped mark. A second viewer shared an encounter with a cicada that attempted to probe her finger with its beak while she was holding the cicada during a “show and tell” demonstration with some children.

See the black proboscis or beak of the cicada between its front legs? Watch as it pushes its beak into the tree to find the vascular element called xylem which will be its source of liquid food for the next several weeks.

So, let’s dive into these questions about biting and stinging cicadas and see what might be afoot. We all learned in grammar school that one commonality of animals is that they are heterotrophs, that is, they cannot produce their own food but instead must eat other things for their sustenance. And when we think about animals eating, we think about biting, right? Biting usually involves something like what we humans do, jaws with mandibles removing chunks of food. Many insects like grasshoppers, beetles, wasps, and caterpillars have jaws that remove hunks of flesh or foliage as they feed. However, in many clans of insects, these jaw-like mouthparts have morphed dramatically through time into more soda-straw-like mouthparts, called piercing or sucking mouthparts, with the descriptive name of beak or proboscis. The beak has internal channels; one is used to remove liquid food from plants or animals which they feed upon, and another channel is used to inject saliva into the food item. Insects with sucking mouthparts include disagreeable rascals like bed bugs, mosquitoes, stink bugs, and lanternflies. Cicadas also have sucking mouthparts used to imbibe xylem fluid from plants on which they feed. So, do cicadas bite? Technically, you cannot bite with sucking mouthparts but you can suck and yes, cicadas do suck. Obviously, the next question is “do they suck on humans or pets?” The answer as far as I am aware is no. I have never heard of any human or animal losing blood to a sucking periodical cicada. These are obligatory plant feeders. The person mildly assaulted by a cicada shared that it did not break her skin. Also, she disclosed that the cicada had been confined for a long time and maybe it was tired of being held by a human. Who knows?

Young saplings and recently transplanted trees growing rapidly in the open are often heavily damaged by cicadas.

Well, what about stinging? Let’s dive into that. Stinging insects like bees, ants, and hornets, do so with an appendage at the tip of their abdomen called an ovipositor. Queens of these social insects use their ovipositor to lay eggs that hatch into workers. Workers are tasked with the onerous job of defending the colony. The ovipositors of defensive workers are connected to glands that produce venom, powerful chemical cocktails designed to bring intense pain to Winne the Pooh or other interlopers intent on raiding the colony for honey or brood. The ovipositor of most other insects is an appendage used to deposit eggs in a place where offspring can develop and thrive. As is the case with cicadas, ovipositors of these insects lack venom. Periodical cicadas use their ovipositor to cut slits into the tissues of plants, primarily trees and shrubs, where eggs of the next generation of cicadas develop before nymphs hatch and drop to the earth. As you might surmise, these ovipositors are stout and sharp enough to pierce the bark of a branch. Perhaps the person assaulted by a cicada was the unwitting victim of a misguided female cicada who mistook a human shoulder for a place to deposit eggs. Animal behavior is rife with mysteries and evolutionary mistakes, some for the better and some for the worse. If this assault was an attempt to lay eggs in a human rather than a plant, you can bet these foolish egg-laying genes will not last long in the reign of cicadas.

Female cicadas use saber-like ovipositors to cut slits in the bark of small branches. These slits are called egg-nests. Watch as the female cicada moves her ovipositor in and out of an egg-nest where she deposits 20 to 30 eggs. She creates dozens of egg-nests which line small branches throughout the canopy of trees she visits. In some cases, weakened branches break and leaves die, creating so-called “flags” hanging throughout the crowns of cicada laden trees. Young saplings and recently transplanted trees growing rapidly in the open are often heavily damaged by cicadas.

Wrapping trees in netting will prevent periodical cicadas from damaging branches of young trees.

My take is that the chances of being probed by the beak of a cicada or assaulted by a crazed, egg-laying female are very small. However, for the millions of homeowners that might be visited by periodical cicadas there is one potentially significant problem. This “dark side” of periodical cicadas manifests itself if you have small saplings or have recently installed young trees in your landscape. Egg-laying cicadas will slice branches to insert their eggs into egg-nests. This causes the tips of many branches to wither and sometimes die. Dying and dead terminals droop, resulting in a type of tree injury called flagging. Some injured terminals break and fall to the ground. Branches that do not break may eventually heal, but the wound-site may form a gnarly irregular swelling on the branch. Which plants are most likely to be affected? The bad news here is that periodical cicadas are broad generalists. Miller and Crowley (1998) studied 140 genera of trees at the Morton Arboretum and found more than half sustained injury caused by ovipositing females. Among the most severely affected were ones common to landscapes in the DMV, including Acer (maple), Amelanchier (shadbush), Carpinus (hornbeam), Castanea (chestnut), Cercidphyllum (katsura), Cercis (redbud), Chionanthus (fringe tree), Fagus (beech), Quercus (oak), Myrica (bayberry), Ostrya (hophornbeam), Prunus (cherry) and Weigela (weigela). Another study by Brown and Zuefle (2009) of 42 woody plant species added several new genera to the list and found all but 10 species were used by cicadas to lay eggs. Small rapidly growing trees with longer, more open branching habits found in young saplings were more heavily used for egg-laying. Trees at the edges of forests with rapidly growing branches exposed to sunlight often sustain more cicada injury. While ovipositional injury poses a threat to newly planted trees, for older and well-established trees flagging and limb breakage may occur in the short term, however, studies indicate that the long-term threat to tree vitality is minimal (Miller and Croft 1998).

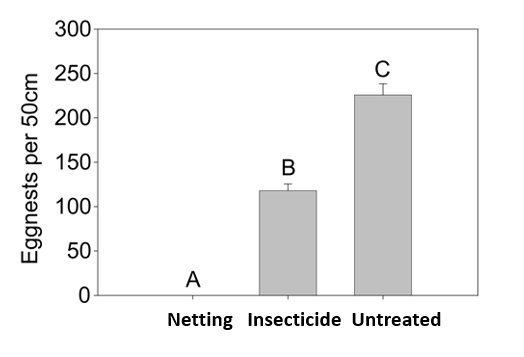

How can you mitigate damage caused by ovipositing Brood XIV cicadas on young trees in your yard? Unfortunately, sometimes our knee-jerk reaction is to grab a can of insecticide and start squirting when we see a bug. In the case of periodical cicadas, studies have shown that the most effective deterrent to egg-laying cicadas is to wrap your saplings in netting that prevents females from laying their eggs. Ahern et al. (2005) found that linden saplings protected by netting with openings of 1 cm (0.4 inches) prevented cicadas from laying eggs whereas saplings treated with systemic insecticides or those left untreated received several hundred egg-nests along their branches.

Young linden trees protected by netting had virtually no egg-nests laid in their branches while those treated with a systemic insecticide or left untreated had hundreds of egg-nests deposited in their branches. Data from Ahern et al. 2005.

In future episodes we will explore when Brood XIV cicadas might appear and learn more about these strange and remarkable insects.

To learn how to properly protect your tree with netting from egg-laying cicadas, please watch this clever video.

Acknowledgements

Great references for this episode include “Does the periodical cicada, Magicicada septendecim, prefer to oviposit on native or exotic plant species?” by W. P. Brown and M. E. Zueffle, “Effects of oviposition by periodical cicadas on tree growth” by K. Clay, A. L. Shelton and C. Winkle, “Periodical Cicada (Magicicada cassini) Oviposition Damage: Visually Impressive yet Dynamically Irrelevant” by W. M. Cook and R. D. Holt, “Effects of periodical cicada ovipositional injury on woody plants” by F. Miller and W. Crowley, “The ecology, behavior and evolution of periodical cicadas” by K. S. Williams and C. Simon, and “Comparison of Exclusion and Imidacloprid for Reduction of Oviposition Damage to Young Trees by Periodical Cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadidae)” by R. Ahern, S. Frank, and M. Raupp. Thanks to two anonymous viewers who shared their stories with me and to my friends at the Weather Channel for allowing me to share cicada stories with others.