Yes Virginia, there is a spider ornament on my Christmas tree.

Each year as we put the finishing touches on our holiday tree, a serious debate arises regarding the quantity of tinsel necessary to complete the task. During this year’s deliberation, I pondered the murky origins of tinsel. To some, the silvery strands of unknown composition evoke images of glistening icicles or shimmering crystals of frost on evergreen branches. But how did tinsel become part of a holiday tradition in so many households?

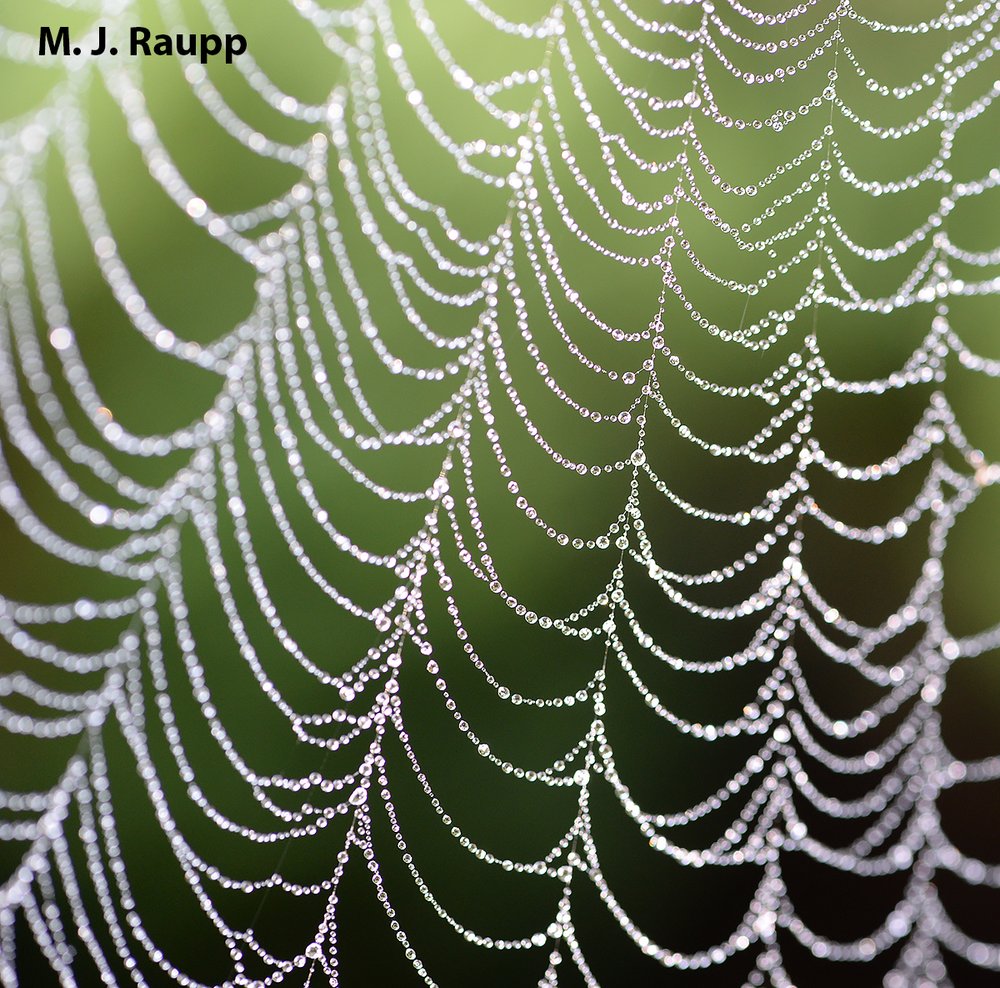

When morning dew glistens on silken strands, it's not hard to imagine why shimmering tinsel conjures thoughts of beautiful spider webs.

To aficionados of arachnids, the tradition of festive tinsel has several different origins. One Christian story tells of Mary’s harrowing escape from Roman soldiers as she and Jesus hid in the hills near Bethlehem. With Herod’s legion in hot pursuit, Mary entered a cave seeking refuge. Spiders quickly sealed the entrance with silk and when soldiers arrived and saw the undisturbed webs, they disregarded the cave as a hideaway and continued their search elsewhere. Often-maligned spiders saved the day! Since that time, tinsel has been strung on Christmas trees to represent a glistening spider web and to commemorate the spiders’ miraculous deed. Other tinsel legends from Germany and the Ukraine tell of spiders escaping the lethal brooms of housekeepers by hiding in dark corners of the home during preparations for holiday celebrations. After exiting their redoubts on Christmas Eve, spiders excitedly explored the evergreen trees that had been brought inside and then left behind glorious cloaks of gossamer webs. When Father Christmas arrived that night and saw the gray spider webs, he miraculously changed them into sparkling silver strands, much to the delight of families who viewed the trees on Christmas morning. Since that time, tinsel has been strung as a symbol of the remarkable event.

Watch as the beautiful spined micrathena carefully places each strand of silk in her gossamer web.

In the warmth of a home, spiderlings may soon hatch from this egg sac and decorate my tree with silk.

Many spiders survive winter’s chill as eggs protected in silken sacs. If the spider’s last haunt was a spruce or fir, then egg sacs may enter homes as stowaways on Christmas trees. In the warmth of holiday homes, eggs hatch and humans may be recipients of dozens of unexpected visitors in, on, and under the Christmas tree. If you discover a spider egg sac on your Christmas tree or fresh evergreen boughs, simply pluck off a small piece of the infested branch and place it along with the egg sac outside on a shrub. This will allow the spiders to hatch just in time to deliver a deferred holiday gift of pest control in your garden.

Other common visitors that may enter homes with holiday greenery include egg cases of praying mantises such as those of the Carolina mantis, European praying mantis, and Chinese praying mantis. In temperate areas like the DMV, these apex predators spend the winter as eggs in Styrofoam-like masses called ootheca. In spring when temperatures warm and prey are once again abundant, mantis eggs hatch and hungry nymphs get busy ridding your farm, garden, or flower bed of pests. For a bug geek, the notion of hundreds of tiny mantises hatching on a holiday tree might bring an unusual kind of holiday cheer, but for most folks, all those tiny mouths to feed might be somewhat overwhelming. So, before you choose a holiday tree or other greenery to bring into your home, do a quick inspection and remove any mantis egg cases and leave them outdoors where they will provide pest cleanup in spring.

Spider egg sacs like these of the Basilica spider on holly sometimes inadvertently enter homes.

Egg cases of praying mantises can also find their way into your home. If you find one, place it outdoors in your garden and reap the benefit of this apex predator next spring.

Several insects and arachnids spend the winter on greenery that you might bring into your home. When you choose your holiday tree, inspect it before you bring it indoors. Look for egg cases of Chinese praying mantises, Carolina mantises, and European praying mantises. Egg cases like this one of the basilica spider may be on a thread of silk or some may be small white fluffy wax tufts on branches. If you live in a region with spotted lanternflies, scrape off egg masses on the bark and destroy them. Some sucking insect pests with white wax, like adelgids on Douglas firs or pines and tiny white scale insects on needles, will not survive in your home and will not cause problems.

In areas invaded by spotted lanternfly, we know that adults lay eggs on many types of trees and structures. Scientists at Penn State recommend inspecting the trunks of holiday trees and scraping off any egg masses of lanternflies lest they hatch in the warmth of your living room and bring some holiday mischief to your home. Other lanternfly relatives, sucking insects such as scales on pine needles and adelgids on branches and bark of pine and spruce, may also accompany greenery into your home. They can be recognized by the white wax that covers their tiny bodies. Even if these insects enter your home, the conditions inside your house are not likely to support their establishment or survival.

Bug of the Week wishes one and all a joyous Holiday season and a wonderful New Year!

Acknowledgements

We thank Jason and our friends at the Weather Channel for providing the inspiration for this episode. The interesting article “Insects on Real Christmas Trees” by Michael J. Skvarla was used as a reference.

To learn more about spiders and associated legends and stories of Christmas, please visit the following website: http://www.willowmoonmarket.com/legends.html#Tin

To learn a bit more about dealing with insects and spiders that enter your home in winter, please click on this link for a story on the Weather Channel, and visit the following website: https://extension.psu.edu/insects-on-real-christmas-trees