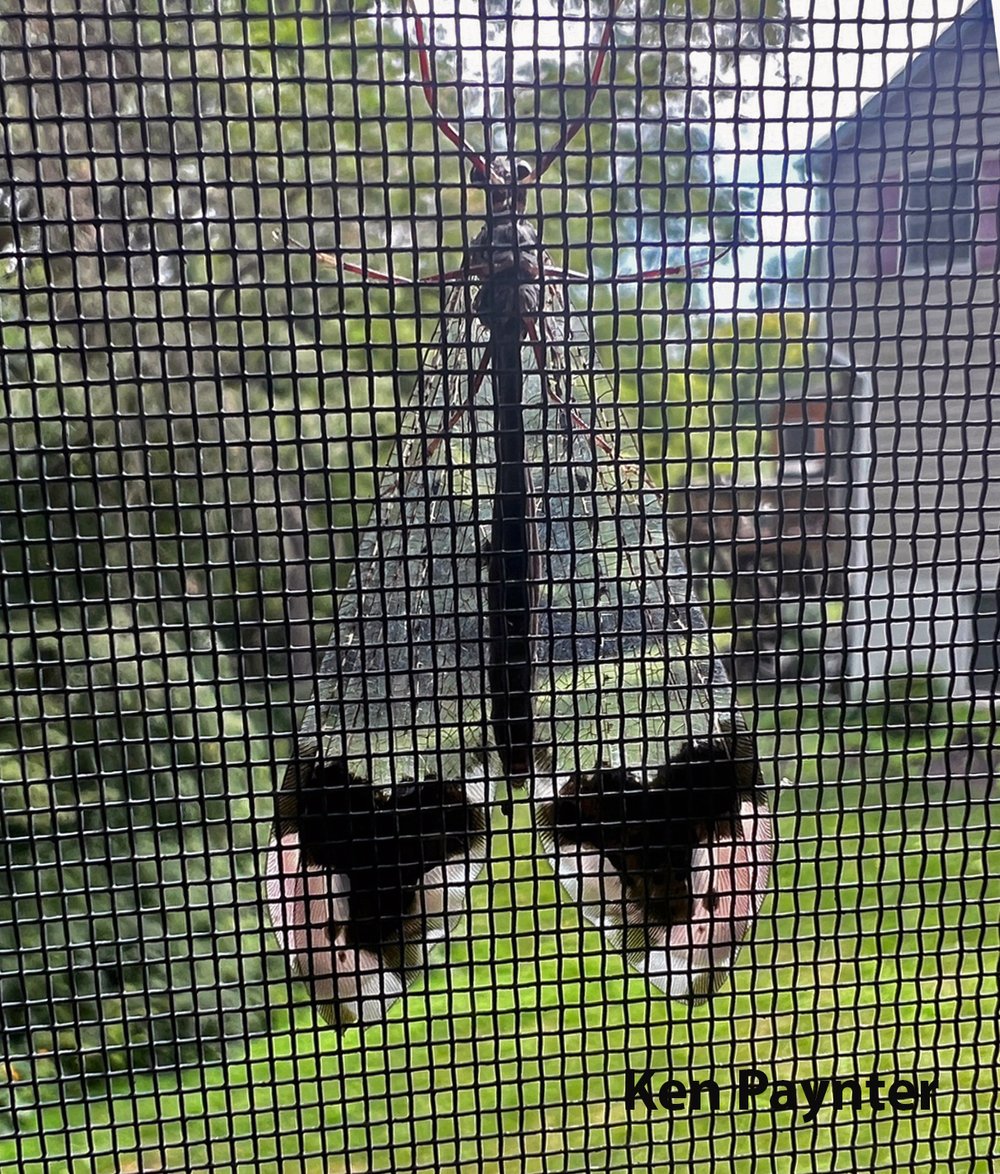

This gorgeous adult Glenurus antlion made a surprising guest appearance on a window screen. Image credit: Ken Paynter

Conical pits in dry soil spell danger for ants and other small ground-dwelling arthropods. Death awaits at the bottom of the antlion’s pit.

Some of you may recall a memorable desert scene from George Lucas’s Return of the Jedi were a terrifying multi-toothed creature called a Sarlacc inhabited a pit on Tatooine and dined on hapless Jedi Knights. Each year miniature versions of Sarlaccian pits appear in the dusty desert beneath the overhang of my tractor shed. These craters, ranging in diameter from the size of dimes to larger than quarters, mark the killing field of antlions, the larval stage of nerve-winged insects (Neuroptera) known as Myrmeleontidae. One of my curious pastimes is to watch ants, beetles, and other small ground dwelling arthropods stumble into the craters and tumble down the slope. At the base of this cone of death lies the ferocious predatory antlion.

Wicked jaws of the antlion larva capture victims and drain their blood. Jaws are also used to construct the antlion’s pit and flick sand to capture prey.

The antlion larva, affectionately known as a doodlebug, constructs its funnel-shaped trap by backing into sandy soil and carefully flicking soil particles with its mouthparts until a symmetrical pit forms. Small ground-dwelling arthropods like ants fall into the pit and tumble to the bottom. At the base of the pit just beneath the sand, the antlion awaits its prey. Sensing that someone has dropped in for dinner, the antlion flicks sand particles upward until the victim tumbles to the bottom of the pit where the ill-fated quarry meets a lethal embrace with powerful jaws of the antlion. The victim is often dragged entirely beneath the sand as the antlion enjoys its feast. Jaws of the antlion bear a groove used to channel blood from the living victim to the belly of the beast. After consuming the liquid portion of the prey, the antlion tosses the carcass from the pit with a snap of its head. Occasionally a large or lucky potential victim will evade the first strike and attempt a desperate scramble for freedom up the slope. To foil the escape, the antlion again flicks sand from the base of the cone towards its prey. The displacement of sand creates a Lilliputian avalanche carrying the prey down slope into the grasp of the antlion.

In the dry soil beneath the overhang of a shed, small pits in the soil mark the kill zone of antlions. Watch as an antlion larva disappears beneath the earth. Once buried it constructs a conical pit to trap its prey. Among the carcasses of a beetle and a daddy-long-legs, a hapless ant attempts a desperate scramble out of the antlion’s pit, all to no avail. Soon the ant will be pulled underground and drained of its blood. The ant’s carcass will be added to those of other victims near this pit of despair. The beautiful adult stage of an antlion is often mistaken for a dragonfly or other winged insect.

Adult antlions sometimes frequent vegetation in my garden. Females will find mates and return to dry sandy soils around my home to lay eggs in the soil.

Adult antlions are rarely seen, but are often mistaken for a damselfly or dragonfly. Feeding habits of these beautiful creatures are largely unknown other than that they consume soft-bodied insects and pollen. They are often attracted to outdoor lights at night. These delicate insects lay eggs in sandy soil where eggs hatch into subterranean monsters. Upon completing development, antlions spin silken cocoons in the soil where the transformations from larva to pupa to adult takes place. So, while hiking in the desert, if you come across a deep conical pit, stay well back from the edge lest you tumble in. You never really know what waits at the bottom.

Acknowledgements

References for this Bug of the Week include “Effects of slope and particle size on ant locomotion: Implications for choice of substrate by antlions” by Jason Botz, Catherine Louden, Bradley Barger, Jeffrey Olafsen, and Don Steeples, and “Immature Insects” by Frederick Stehr. The inspiration for this Bug of the Week came from Ken Paynter who shared the wonderful image of Glenurus with us.