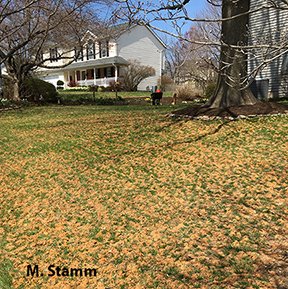

Warm weather puts boxelder bugs on the move. You may see one or buckets of boxelder bugs outside your home in coming weeks. Image credit: Margi Raupp

Hordes of boxelder bugs gather on the outside of a home to enjoy a day in the sun – the perfect Spring Break for a boxelder bug! Bet you’re glad this isn’t your house!

Two weeks ago, we met a pesky home invader, the brown marmorated stink bug, as it stirred from its indoor redoubt and annoyed inhabitants of a home while attempting to escape outdoors to the natural world. As temperatures once again soared into the 70s, we turn our attention to reports of hordes of another rascal, boxelder bugs, festooning a suburban home. Boxelder bugs are members of the order Hemiptera, a.k.a. the “true bug” clan, characterized by their sucking mouthparts and gradual metamorphosis. Two years ago, a bug-friendly neighbor inquired about vast numbers of boxelder bugs aggregating on their patio and the sunny side of their house. As our friends opened and closed doors, these rascals snuck inside for reasons known only to themselves and Mother Nature. Last week, a family member in eastern Pennsylvania sent images of dozens of boxelder bugs lounging on the side of their house. How did these rascals arrive and why are they now active?

Ok, boxelder bugs are a little creepy when you see hordes of them on the side of the house or the tool shed. (private)

When not feeding on seeds, boxelder bugs will dine on bird poop. Yum!

Here’s the story. Depending on geographic location, boxelder bugs complete one to three generations each year. They survive winter’s ravages hiding in cracks and crevices beneath shutters and under siding, and by entering other access points in structures. In natural settings outdoors, winter refuges include loose bark or hollows of trees, tangles of brush, and voids under rocks. During the last few weeks as temperatures soared into the upper 60s and 70s here in the Washington metropolitan region, boxelder bugs emerged from these redoubts and made their presence known inside homes as they sought a way out. On the exterior of homes, they aggregated in large numbers to soak up thermal energy from the sun. Spring and summer are times for foraging on a wide variety of plants, including seeds of their namesake tree, boxelder, as well as other members of the maple clan. Both adults and nymphs feed on propagules of many different kinds of seed-bearing trees and on the juicy tissues of many other landscape plants.

Seeds from this old maple tree support a population of boxelder bugs that sun themselves on the side of a home on warm spring days. Wanderers sometimes enter homes, creating a nuisance. Others battle as they feed on a maple seed on the ground. Males and females pair off, and after mating females deposit eggs in many places, including sides of buildings. Wingless nymphs that hatch from eggs feed on a wide variety of plants.

Female boxelder bugs deposit eggs in clusters. Tiny nymphs will hatch and move to the ground to consume seeds and other plant tissues.

After gaining sufficient nutrients, mated females deposit eggs on a wide variety of substrates on the ground and also on human-made structures. In autumn, large clusters of boxelder bugs gather on trees and buildings where they become a nuisance. In the waning days of autumn, they seek winter shelter. They enter homes through cracks in the foundation, gaps in siding around windows or vents, and beneath doors and windows. On cold winter days they are inactive, but as winter retreats and temperatures warm, restless boxelder bugs move about and make their presence known inside and out.

Boxelder bug nymphs are wingless nymphs.

Boxelder bugs are not harmful to humans or pets. They do not bite, sting, or reproduce indoors, however, if you squash them on your drapes or walls, they will stain. So, don’t do that.

To limit the number of boxelder bugs taking up residence in your residence, eliminate overwintering places such as piles of lumber, fallen branches, or other refuges close to the house. Some folks go as far as removing boxelders, other maples, and ash trees from their landscapes to reduce food sources for nymphs and adults. Weatherproofing your home can also help keep these invaders out. Caulk and seal openings where utilities enter the home. Repair or replace door sweeps and seal any openings around windows, doors, or window air conditioners.

If you find them inside your home, you might try this. Simply get out the hand-held vacuum, suck them up, and release them back into the wild. It is wise to choose a liberation point some distance away from your home.

The boxelder bug’s clever mouthparts (proboscis) enable it to feed on seed and plant tissues.

Acknowledgements

We thank Margi, George, Anne Marie, and Dennis for sharing their boxelder bugs, and providing inspiration for this episode of Bug of the Week. The wonderful reference “Urban Insects and Arachnids: A Handbook of Urban Entomology” by William Robinson was used as a reference.