Bedecked in their finest colors of orange and black, Florida predatory stink bugs are now more common in the DMV and other northern states as our world warms.

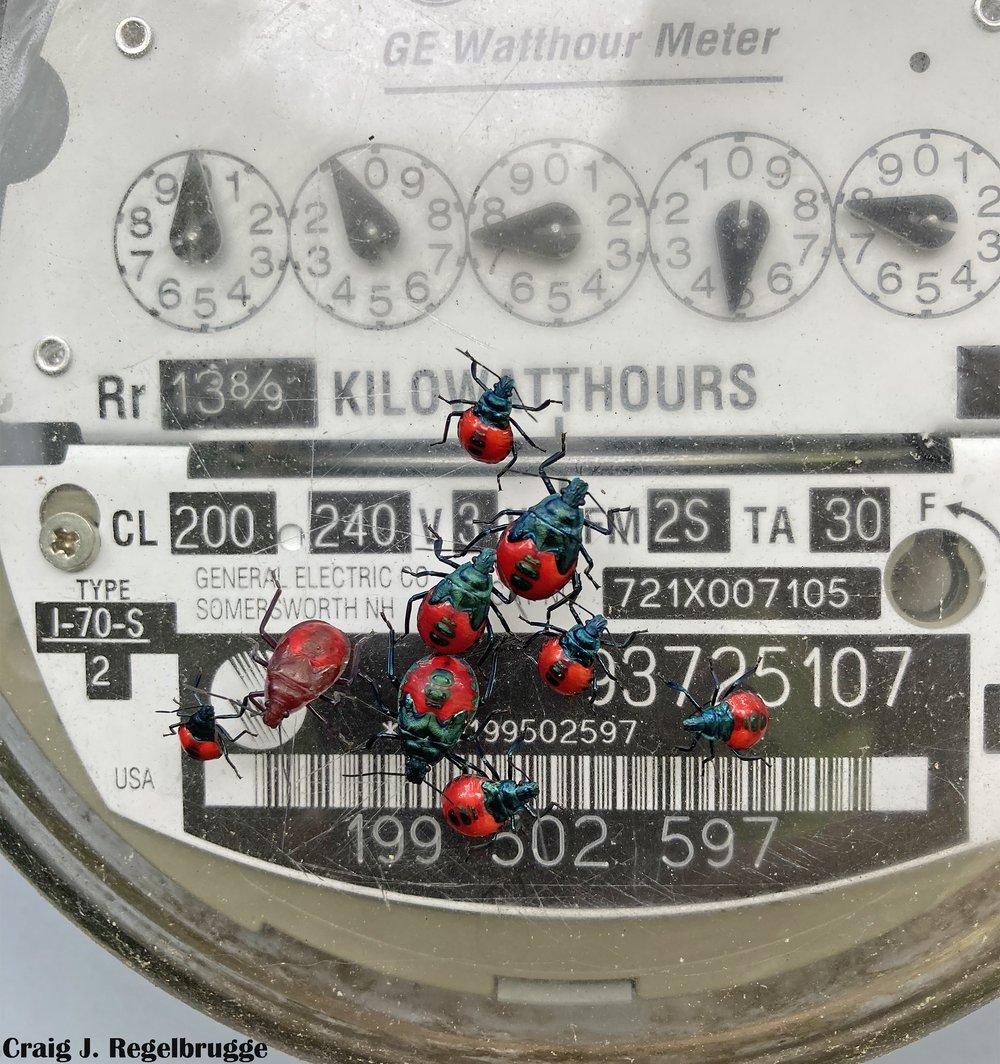

Are utility companies employing Florida predatory stink bugs to do jobs once performed by humans? Image: Craig J. Regelbrugge

Last year was the fifth hottest year in recorded history. This year followed suite with June, July, and August of 2023 being the hottest months ever recorded globally according to the European Union Climate Change Service. Here at home in the United States, if you feel like your town was toastier than normal, you are probably correct as almost 10,000 cities and towns tied or broke daily heat records this year according to the National Weather Service. One of the interesting and ecologically disturbing consequences of climate change is the expansion of the ranges of warm-weather insects to cooler regions where short growing seasons and chilly winter temperatures formerly barred their survival. Last week we met nefarious, collard-crunching harlequin bugs. It should come as no surprise that in addition to plant-eating pests, other insects including beneficial ones have shifted their range. The Florida predatory stink bug is one such beneficial insect that has followed suite and now appears regularly in locations previously thermally off-limits to them.

Florida predatory stink bugs, historically from southern regions, now make regular incursions as far north as New Hampshire and the Dakotas as lethal cold winter temperatures become less frequent. More than a decade ago, in 2012, which was at that time the hottest year on record, Bug of the Week posted an episode noting the unusual discovery of the Florida predatory stink bug sunbathing on the trunk of an elm tree at the University of Maryland. Isolated reports of Florida predatory stink bugs in Maryland date back even earlier than 2012. Last autumn adult Florida predatory stink bugs were seen with regularity in the DMV. Following the second warmest winter ever recorded in the region, it came as no surprise that these fierce predators were back in force in 2023 and numerous reports of this predator surfaced in the DMV.

Last autumn, spooky orange and black Florida predatory stink bugs were spotted on trees and buildings here in the DMV. Were these beneficial denizens of the Deep South able to handle the ‘winter that didn’t happen in 2022/2023’ in this region? Surely looks like it, as developing nymphs and adults were seen throughout our region this summer and autumn. It appears that nymphs of the Florida predatory stink bug have a baffling desire to interpret the dials and readouts on electric utility meters. In a warming world, it looks like they may be here to stay. Video by Michael Raupp and Craig J. Regelbrugge

Color variations in Florida predatory stink bugs range from greenish to black backgrounds bearing orange to reddish spots. Image: Sarah Zastrow

The Florida predatory stink bug is native to tropical and semi-tropical regions ranging from Peru to the United States. Like its cousin the spined soldier bug we met in a previous episode, the Florida predatory stink bug is a generalist. Using a powerful beak to impale and immobilize its prey, it then sucks nutritious body fluids from the victim to sustain growth, development, and reproduction. In addition to consuming caterpillars and leaf beetles in backyard vegetable gardens, both nymphs and adults of the Florida predatory stink bug put a beat-down on important crop pests including brown marmorated stink bugs and kudzu bugs. As record high temperatures continue to build and growing seasons extend in both spring and fall, keep an eye out for these beautiful beneficial predators that are becoming more common here in the DMV and in locations further north.

Acknowledgements

We thank Craig J. Regelbrugge and Sarah Zastrow for sharing images of Florida predatory stink bugs that inspired this episode. The interesting articles “Florida predatory stink bug (unofficial common name), Euthyrhynchus floridanus (Linnaeus) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)” by Frank W. Mead and David B. Richman, and “Feeding Responses of Euthyrhynchus floridanus (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) to Megacopta cribraria (Heteroptera: Plataspidae) with Spodoptera frugiperda and Anticarsia gemmatalis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Larvae as Alternative Prey” by Julio Medal, Andrew Santa Cruz, and Trevor Smith were consulted for this episode. Records from the Maryland Biodiversity Project helped inform discoveries of this predatory stink bug in the DMV.