This pretty yellowjacket nest was found beneath a set of steps near a deck outdoors.

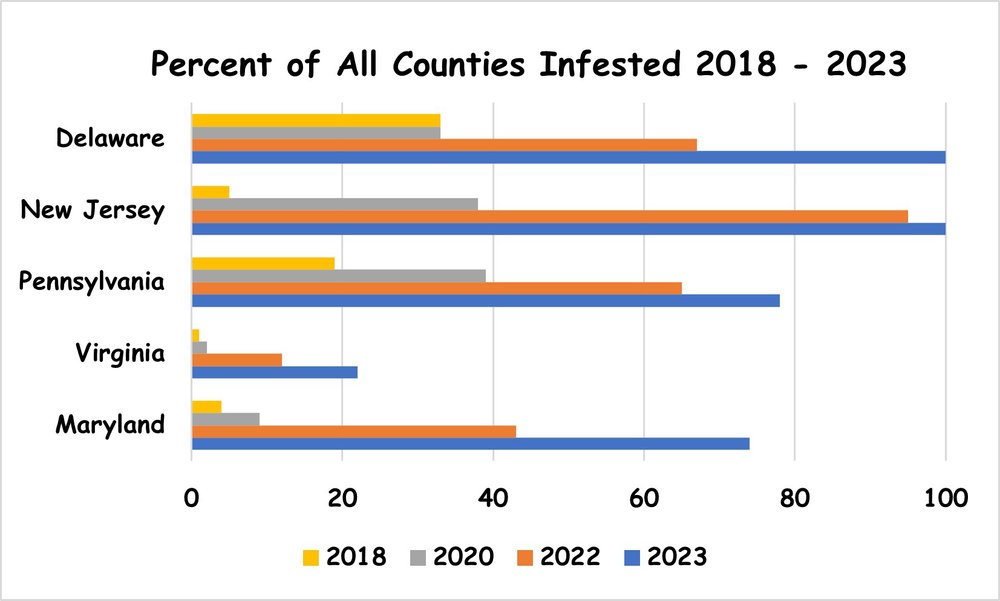

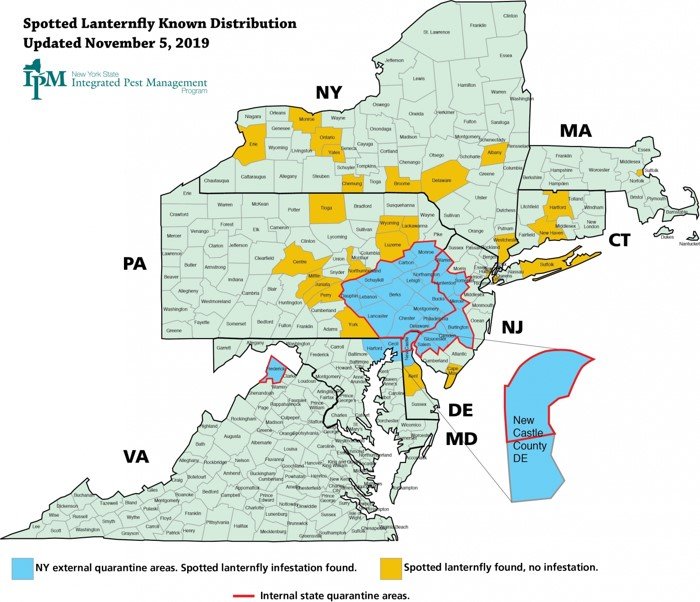

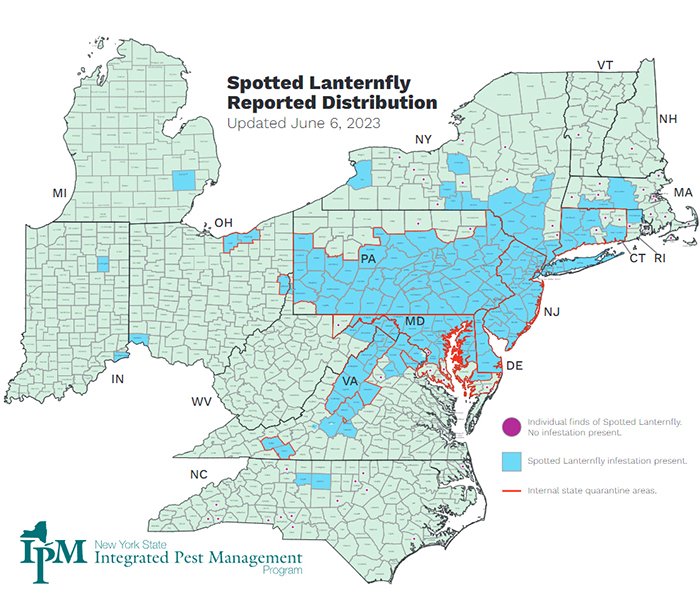

Last week we visited spotted lanternflies as they continued their march through the DMV and other states in the eastern half of the United States. These killers of grape vines are a major nuisance in residential and commercial landscapes by virtue of their creep-me-out vast numbers and the prodigious amounts of honeydew they excrete as they feed. Honeydew is the sticky sweet waste product squirted from the rear-end of the lanternfly as it sucks nutrient rich phloem sap from a plant. Honeydew rains down on objects below, fouling fruit, foliage, lawn furniture and slow-moving humans that linger too long beneath trees. This carbohydrate rich liquid provides a substrate for a fungus called sooty mold, a black cloak that coats and disfigures underlying objects. Although sooty mold is not pathogenic, it diminishes the plant’s ability to capture energy from sunlight thereby reducing photosynthesis and impairing growth. As we learned in a previous episode, lanternfly honeydew is a favored food source for many kinds of stinging insects including bees and wasps. Recently, a large landscape maintenance firm in the DMV made an unprecedented purchase of cans of wasp and hornet sprays at a local hardware store. When asked “why so many”, the landscaper replied something like “the landscaping crews are running into unreasonable numbers of yellowjackets and various wasps as they clean up landscapes.”

On tree of heaven coated with sugary honeydew excreted by lanternflies and cloaked in black sooty mold, yellowjackets, paper wasps, and hornets forage. Along the edge and within a forest conservation area loaded with tree of heaven, several eastern yellowjackets have set up shop. Lanternflies nearby provide a ready source of food. Work and studies within the site have become spicy this summer due to the presence of stinging insects. Could recent reports of elevated numbers of wasp nests be linked to increasing numbers of lanternflies in areas infested with this invader? Only Mother Nature and the wasps really know.

Unlike the nests of bees, the nests of yellowjackets contain no honey or pollen. Yellowjacket larvae eat meat and carbohydrate rich foods gathered by the workers. In this regard, yellowjackets are beneficial because they kill many caterpillars and beetles that are pests in our gardens. By late summer and early autumn, colonies may contain thousands of workers and are often about the size of a football. Under extraordinary circumstances, some nests may persist for more than one year and reach gigantic proportions. There are reports of monster yellowjacket nests in southern states reaching the size of a “Volkswagen Beetle”. Yikes! I sure wouldn’t want to bump into one of those with the lawn mower. Well, as summer wanes towards autumn, colonies of many social wasps including yellowjackets, bald-faced hornets, and paper wasps will operate at a fevered pitch as they try to feed massive numbers of brood in their nests. As we learned in previous episodes, nests are aggressively defended and intruders are attacked with extreme prejudice.

Lil’ Rover demonstrates what happens when you sit on a nest of yellowjackets, but don’t worry, Lil' Rover has thick fur and was not harmed in the making of this video.

The venom of yellowjackets and their kin has evolved to bring maximum pain to vertebrates like skunks that pillage their nests. Encounters with these fierce ladies confirm that their venom brings agony to humans as well. Yellowjackets are capable of multiple stings, but only to a limited extent. Contrary to common belief, they have small barbs on their stingers and some may lose their stingers after an attack. If you are stung, apply ice to the site of the sting to reduce some of the damage and pain. Sting relieving ointments and creams are available in pharmacies and sporting goods stores and may help reduce the pain and itching. If you know that you are allergic and are stung, seek medical attention immediately. If you are stung and experience symptoms such as shortness of breath, difficulty breathing or swallowing, hives on your body, disorientation, lightheadedness or other unusual symptoms, call 9-1-1 and seek medical attention immediately. Desensitization therapy has proven very helpful to many people with allergies to stings of bees and wasps.

In some locations infested with spotted lanternflies, yellowjackets have become huge problems.

At Bug of the Week’s five-acre SLF tracking site, prior to the arrival of SLF a single eastern yellowjacket nest was discovered in the ground in 2021. With the arrival of lanternflies at the site in 2022, two yellowjacket nests were discovered near groves of tree of heaven, and with thousands of lanternflies spewing honeydew in 2023, five colonies of eastern yellowjackets have been discovered at the site to date. Adding even more moments of shock and awe to work at our study site are bald-faced hornets, which constructed an additional nest in a pile of brush. It could be coincidental that both lanternflies and stinging wasps are on the uptick due to some other environmental circumstance rather than being linked. At this point in time, we simply do not know. If you encounter a yellowjacket or bald-faced hornet nest and the nest is unlikely to be encountered by humans or pets, you may simply leave it alone. As mentioned before, these wasps help reduce populations of pests. If the nest is in a place that threatens you, children, or pets, you may consider eliminating it. Commercial pest control operators can assist you in this. I have purchased aerosol sprays, applied them according to instructions on the label, usually at night or in the evening, and had excellent success. Please be careful around these fierce ladies or you might feel their wrath.

Acknowledgements

Bug of the Week thanks Dr. Nancy Breisch for sharing her expertise and knowledge about stinging insects. We thank bold landscape managers and arborists for providing inspiration for this episode and Randy Taylor for sharing his pretty yellowjacket nest with us.