Dispersal flights by spotted lanternflies are underway. In the human-built environment many spotted lanternflies will fail to reach suitable host plants and will perish like this one, crushed on a sidewalk.

Near a grove of heavily infested Tree of Heaven, a short flight into a forest brings a spotted lanternfly to a new host tree suitable for growth and reproduction.

On a stiflingly hot afternoon last week in the parking lot of a large suburban mall, I was treated to a remarkable and somewhat macabre phenomenon playing out in a dozen states in the eastern half of the US where spotted lanternflies engage in their annual dispersal flights. Scientists in the invaded range here in the US and in the native range in Asia have long observed the late summer peregrinations of spotted lanternflies as they take wing on hot summer days. Flights which may cover hundreds of yards are thought to carry legions of unmated female lanternflies to new host trees where they will mate, feed and develop eggs, prior to depositing eggs of the next generation. In the natural world, one full of delectable, nutritious host plants including a favored host, the invasive Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), taking a short flight to find a high-quality source of food for you and your offspring sounds like a fine idea. Furthermore, if hungry predators like mantises and assassin bugs or parasitic wasps have discovered you and your gang on your natal tree, getting out of Dodge and finding a new tree on which to procreate makes a lot of sense.

But what happens in an unnatural world, the human-built world where a mile of asphalt separates you from the nearest Tree of Heaven one of your preferred hosts for dining and developing? Here’s what I saw. At a shopping mall complex, scores of lanternflies apparently mistook large vertical surfaces of buildings lining the parking lots as hospitable places to land after departing their birth trees, which lined the perimeter of the asphalt desert. One fetching brown wall of a department store seemed to attract an overabundance of lanternflies, which roamed the bark-like cement surface apparently looking for a place to insert a beak. Lacking vascular tissues on which spotted lanternflies feed, these walls were a particularly bad choice to settle in for a meal. For them, starvation was just around the corner. Less fortunate lanternflies crashed into clear plate glass windows or concrete panels and fell onto sidewalks where busy parents buying back-to-school supplies brought a quick end to their puny lives. One eagle-eyed shopper exiting a store spotted a hapless lanternfly on the ground, exclaimed “oh, that’s a lanternfly, we’re supposed to squash them”, and proceeded to do so with a quick two-step. Another lady emerged from a car with two teenagers on their way to see a movie. A wayward lanternfly landed on her son. The mother grabbed the lanternfly, which displayed its gorgeous hindwings, and said “oh, look how pretty this is, I can’t hurt you.” She launched the insect back into the sky. This fascinating contrast reflects societies’ approach to lanternflies, other invasive insects, and sometimes insects in general. Some love them, some despise them, and many are somewhere in the middle.

Spotted lanternflies are on the wing to find new host plants, bringing them in contact with the human-built world where they will wander buildings and benches in search of food. Many will perish of starvation or dehydration on sidewalks and in parking lots. Others will be squashed beneath feet and automobile tires. Some may visit shoppers and diners briefly before flying off, while others will be snared and killed by urban spiders. Before you leave a parking area infested with lanternflies, inspect your car to make sure these clever vagabonds are not hitching a ride with you.

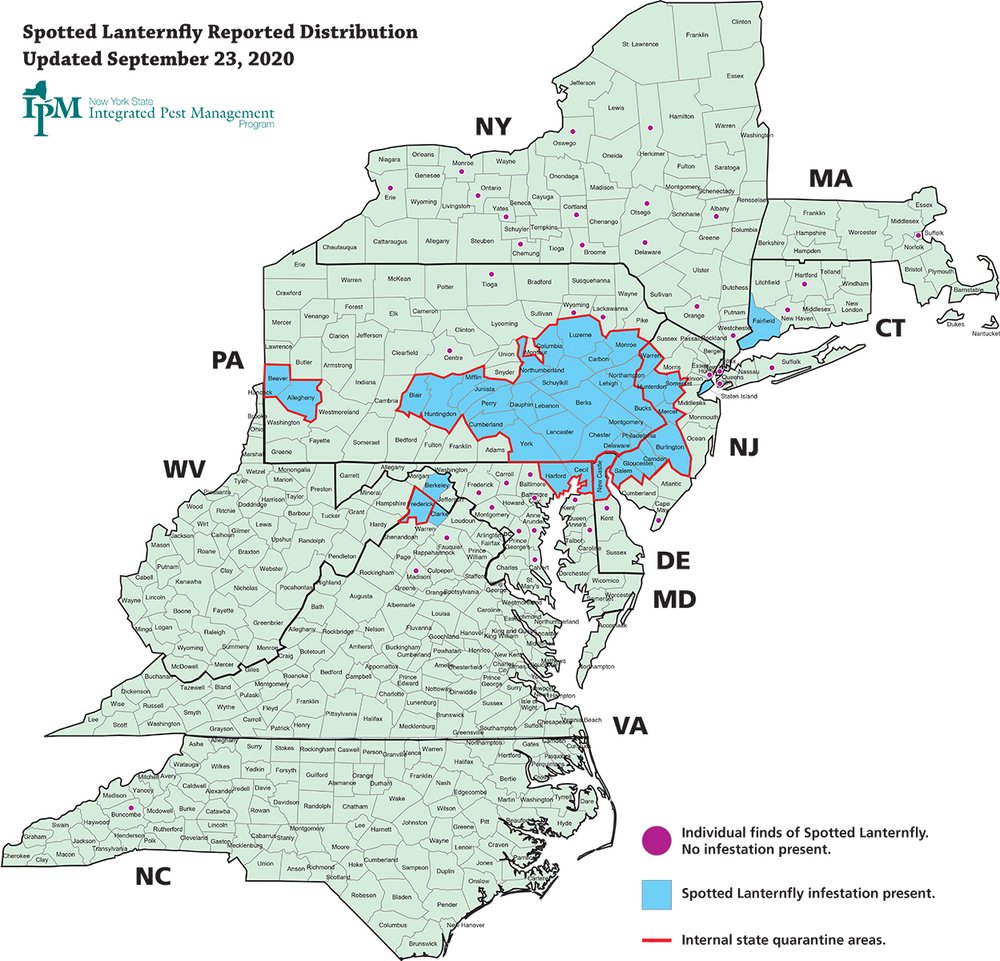

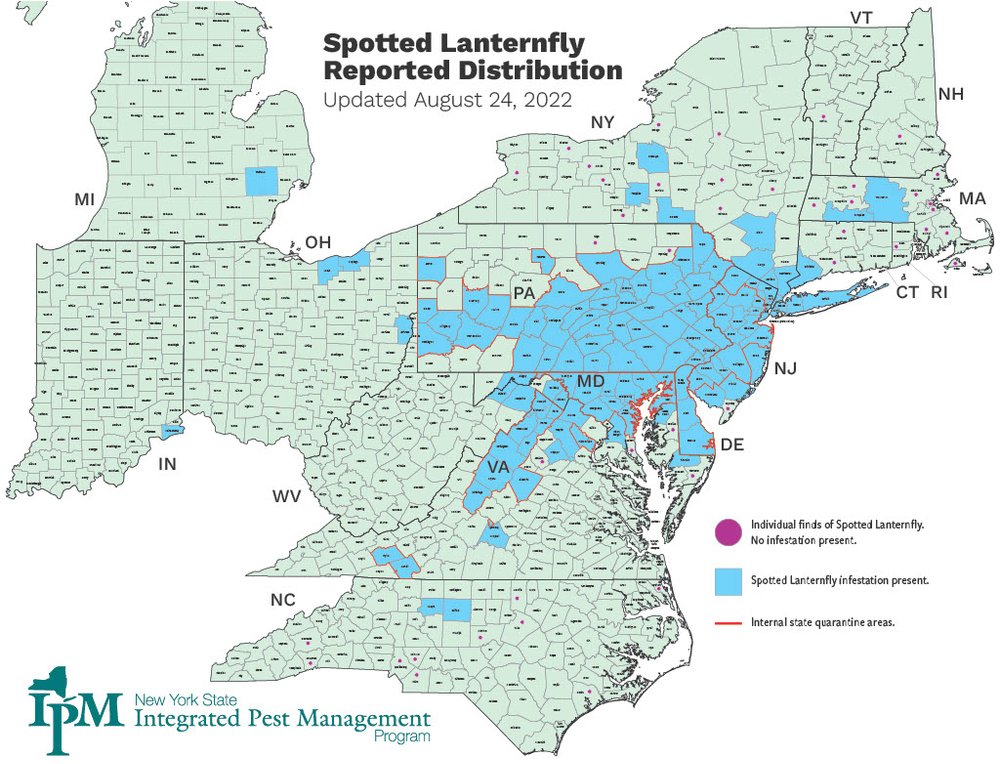

Excepting some form of divine intervention, spotted lanternflies have likely become unwanted but permanent residents in our country. In 2017 during the early stages of the lanternfly onslaught, we reported that more than a million lanternflies had been killed by volunteers in Berks and surrounding counties in Pennsylvania. Despite these herculean efforts, in the intervening five years, lanternflies have spread and established breeding populations in a dozen states, more than eighty counties, and have been detected almost five hundred miles from the place of their initial detection. Here in Maryland, we jumped from 2 infested counties in September of 2020 to 14 infested counties in August of 2022. Lanternflies are on the move.

This map charts the distribution of spotted lanternflies in the United States in September of 2020. Credit: New York State IPM.

The most recent map of the distribution of spotted lanternfly in the United States in August of 2022 shows a remarkable increase in the number of infested states and counties. Credit: New York State IPM.

Despite what you might have heard on television or read somewhere, squashing a few lanternflies in a parking lot in Maryland is unlikely to reduce the abundance of this pest. The vast majority of lanternflies you encounter outside a department store are doomed. In the wild, a diverse complement of predators and pathogens, part of Mother Nature’s hit squad, are already waging war on spotted lanternflies. These beneficial organisms have played important roles in putting a beat-down on other invasive pests like the brown marmorated stink bug. Remember that pest and how things have changed in the last two decades here in the DMV? In addition, clever scientists of the USDA are evaluating enemies of the lanternfly from the lanternfly’s native range in Asia. If these beneficial insects clear rigorous hurdles and pose no threat to our indigenous fauna, they will be released to join the battle against lanternflies.

What should you do if you spot a spotted lanternfly when you stop in a parking lot in Maryland while on a trip to Colorado? Be sure to carefully inspect your vehicle both inside and out to avoid transporting a stowaway to a new location. If you are simply stopping for groceries before heading home and you live in a generally infested county, squashing a lanternfly may save the doomed lanternfly from a miserable death by starvation or being run over by a car. If you live in a county or location where spotted lanternfly is not known to infest and reproduce, like the District of Columbia or Napa County, California, and think you found a spotted lanternfly, by all means squash it and bring a swift end to its dastardly life, but don’t just toss it out. Please, take a photo of it, place it in a zip-lock bag and send it or the image to your local department of agriculture or nearest university extension service for identification. We need to know what new locations this rascal has invaded to make sound management decisions. Maybe you can be the one to help stop this crafty hitch-hiker from setting up shop in your hometown at least for the time being.

Acknowledgements

We thank several shoppers and movie-goes in Hagerstown, Maryland for providing inspiration and video footage used in preparation of this episode. The great article “Flight Dispersal Capabilities of Female Spotted Lanternflies (Lycorma delicatula) Related to Size and Mating Status” by Michael S. Wolfin, Muhammad Binyameen, Yanchen Wang, Julie M. Urban, Dana C. Roberts, and Thomas C. Baker provided information on dispersal behaviors of lanternflies. Thanks to Brian Eshenaur and the entire team at the New York State Integrated Pest Management Program of Cornell University for providing the updated maps of spotted lanternfly distribution in the US.

To learn more about USDA’s efforts to discover beneficial insects with potential to reduce populations of spotted lanternflies, check out this website: https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publication/?seqNo115=338695

To learn more about hitch-hiking spotted lanternflies, please visit this episode of Bug of the Week: https://bugoftheweek.com/?offset=1600693536810&reversePaginate=true

To learn more about spotted lanternfly flights, please click on this link: https://www.psu.edu/news/impact/story/spotted-lanternfly-collective-flights-late-summer-not-dangerous-public/

To see spotted lanternflies in flight, please click this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7MqmWHodMN8

To hear a recent broadcast about spotted lanternflies in the DMV on public radio, please click this link: https://www.wypr.org/show/on-the-record/2022-08-25/the-invasive-spotted-lanternfly-and-park-students-in-the-arctic