The last few decades have seen significant advances in our understanding of microbial diversity. Consistent improvements in available technologies and methods for study, both molecular and ultrastructural, have allowed researchers to look further and deeper than they ever could before. Not only have they identified taxa that were previously unknown, they have been able to develop a much better understanding of how microbial taxa relate to each other. Among the fields that has seen particularly remarkable advances has been the study of the picoplankton, that component of the marine plankton comprising organisms less than two or three microns in size. Much of the picoplankton, of course, is made up of bacteria but another significant component is species of microalgae belonging to the group known as heterokonts or stramenopiles.

Schematic diagram of motile bolidophyte cell, from Guillou et al. (1999).

Heterokonts are a major clade of eukaryotes that are commonly characterised by cells bearing anterior pairs of morphologically distinct cilia. One of the cilia is longer and bears rows of hairs referred to as mastigonemes; the other, shorter cilium is usually smooth. Many heterokont species are photosynthetic and belong to a subclade of the heterokonts known as the ochrophytes. For most people, the best known ochrophytes will be the often-decidedly-not-microbial brown algae such as kelps. However, ochrophytes also include a broad diversity of microbial forms. Most ochrophyte cells share a characteristic golden-brown coloration owing to the presence of yellowish pigments such as fucoxanthin as well as the more standard chlorophyll.

Recent molecular studies have supported a division of the ochrophytes between two major clades. On one side are the brown algae and their closer microbial relatives. In the other clade are those ochrophytes more closely related to the

diatoms. Appropriately enough, this latter clade was dubbed the Diatomista by Derelle

et al. (2016). Other than the diatoms themselves, most representatives of the Diatomista belong to the picoplankton. For the most part, diatoms have lost the cilia otherwise associated with heterokonts. The only exceptions are the reproductive sperm cells which have a single anterior cilium bearing mastigonemes (Adl

et al. 2019). The remaining Diatomista commonly have cells bearing one or two anterior cilia (if only one cilium is present, it will typically have mastigonemes). Nevertheless, the basal apparatus of the cilia is reduced, lacking microtubular roots or a rhizoplast, suggestive of an intermediate stage towards total loss (Guillou

et al. 1999). Many also bear a covering of silica scales; enlargement of individual scales may have lead to the evolution of diatom-style frustules.

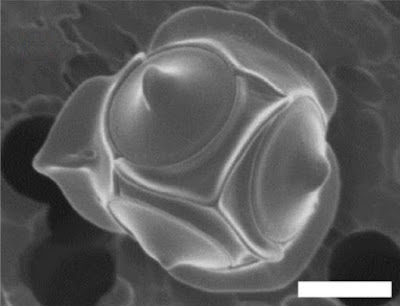

Non-motile cell of Triparma laevis f. inornata, from Kuwata et al. (1987).

The closest known relatives of diatoms are currently classified as the class Bolidophyceae. Motile cells of the Bolidophyceae were first described in 1999 (Guillou

et al. 1999). They possessed two cilia, with the haired cilium directed anteriorly and the smooth cilium directed posteriorly, and lacked silica scales. Nevertheless, they were identified as the sister group to diatoms by molecular data. This was corroborated by the absence of a transitional helix structure at the base of each cilium, a feature shared with diatom sperm cells. Guillou

et al. (1999) commented on the relatively high mobility of the bolidophytes, in contrast to the general expectation that picoplankton should exhibit a reduction in individual cell mobility owing to the difficulty in meeting energy demands.

The concept of bolidophytes shifted somewhat in the 2010s with the isolation in culture of the Parmales, a group of minute eukaryotes that had first been recognised in the 1980s but had long eluded detailed characterisation. These were non-motile cells enclosed within ornate silica scales. Once molecular data become available, researchers realised that 'Parmales' were not just closely related to 'bolidophytes', they were close enough that the two forms could reasonably be included in a single genus (Kuwata

et al. 2018). The exact details of their connection, however, remain uncertain. It seems likely that the flagellate and non-flagellate forms represent alternate forms of single species. But whether we are looking at alternate generations of the life cycle, or whether the flagellate cells are generated in response to particular conditions, remains to be determined.

Skeleton of silicoflagellate Dictyocha speculum, copyright Proyecto Agua.

The remaining members of the Diatomista form a clade currently treated as including three classes, the Dictyochophyceae, Pelagophyceae and Pinguiophyceae. Together they are a diverse array of minute organisms, whether ciliated or amoeboid, naked or carrying organic scales, photosynthetic or heterotrophic or some combination of both. Among the representatives of the Dictyochophyceae are the so-called silicoflagellates, ciliated cells reinforced with a skeleton of (duh) silica. Though only a few species of silicoflagellate are recognised in the modern environment, they have an extensive fossil record extending back to the Middle Cretaceous (Kristiansen 1990). In some places, their preserved skeletons may dominate rock formations. Silicoflagellates appear to have reached their peak in the Miocene, followed by a decline to their modern condition. The exact interpretation of the silicoflagellate fossil record is a long-standing challenge (whether differences in morphology are taxonomic or environmental, for instance) but they hold the potential to tell us much about the history of our seas.

REFERENCES

Adl, S. M., D. Bass, C. E. Lane, J. Lukeš, C. L. Schoch, A. Smirnov, S. Agatha, C. Berney, M. W. Brown, F. Burki, P. Cárdenas, I. Čepička, L. Chistyakova, J. del Campo, M. Dunthorn, B. Edvardsen, Y. Eglit, L. Guillou, V. Hampl, A. A. Heiss, M. Hoppenrath, T. Y. James, A. Karnkowska, S. Karpov, E. Kim, M. Kolisko, A. Kudryavtsev, D. J. G. Lahr, E. Lara, L. Le Gall, D. H. Lynn, D. G. Mann, R. Massana, E. A. D. Mitchell, C. Morrow, J. S. Park, J. W. Pawlowski, M. J. Powell, D. J. Richter, S. Rueckert, L. Shadwick, S. Shimano, F. W. Spiegel, G. Torruella, N. Youssef, V. Zlatogursky & Q. Zhang. 2019. Revisions to the classification, nomenclature, and diversity of eukaryotes.

Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 66: 4–119.

Derelle, R., P. López-García, H. Timpano & D. Moreira. 2016. A phylogenomic framework to study the diversity and evolution of stramenopiles (=heterokonts).

Molecular Biology and Evolution 33 (11): 2890–2898.

Guillou, L., M.-J. Chrétiennot-Dinet, L. K. Medlin, H. Claustre, S. Loiseaux-de Goër & D. Vaulot. 1999.

Bolidomonas: a new genus with two species belonging to a new algal class, the Bolidophyceae (Heterokonta).

Journal of Phycology 35: 368–381.

Kristiansen, J. 1990. Phylum Chrysophyta.

In: Margulis, L., J. O. Corliss, M. Melkonian & D. J. Chapman (eds)

Handbook of Protoctista. The structure, cultivation, habitats and life histories of the eukaryotic microorganisms and their descendants exclusive of animals, plants and fungi. A guide to the algae, ciliates, foraminifera, sporozoa, water molds, slime molds and the other protoctists pp. 438–453. Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Boston. Kuwata, A., K. Yamada, M. Ichinomiya, S. Yoshikawa, M. Tragin, D. Vaulot & A. Lopes de Santos. 2018. Bolidophyceae, a sister picoplanktonic group of diatoms—a review.

Frontiers in Marine Science 5: 370.